The Spark That Ignited the World

The year 1517 witnessed the end of the Fifth Lateran Council. This council made decrees that, if they had only been followed, could have begun the long-awaited reformation of the Church. Near the end of the council, a layman, Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola, told the council fathers that if churchmen did not begin to lead moral lives, then all was lost. If Pope Leo X, said Mirandola, did not punish the immoral clergy, God himself would cut off those rotten limbs and burn them in fire. Leo, however, did nothing.

|

| Johann Tetzel |

Instead, the same year, Pope Leo made a deal with a wealthy German churchman, Albert of Brandenburg. Though he was already the archbishop of Magdeburg in Germany, Albert wanted to be archbishop of the German city of Mainz as well. To do this, however, Albert had to pay an enormous sum of money to the Roman curia. To help Albert come up with the money, Leo allowed him to take one-half of the funds raised in the indulgence for St. Peter's Basilica and use it to pay off his debt to the curia.

Typically, in those days, preachers were sent throughout Europe to offer the indulgence to rich and poor alike. Though these preachers were supposed to tell people that they needed to repent of their sins and go to confession before the indulgence could do them any good, they often did not do so. Instead, they emphasized how much people needed to pay -- the wealthy more, the poor, less, while some only had to promise prayers -- and spoke as if the simple payment of money alone could win the indulgence for people or for family members who were in Purgatory. This was the case with the indulgence Albert of Brandenburg (with the pope's blessing) ordered to be preached in Germany. The Dominican preacher, Johann Tetzel, who preached this indulgence, used this rhyme to convince people to offer their money: "When copper coin in coffer rings / The soul from Purgatory springs."

|

| Martin Luther in 1520 |

In 1517, word came that one of the indulgence preachers was coming to region around Wittenberg, a city in German Saxony. When the Augu-stinian priest Martin Luther, head of the theology faculty at the new University of Wittenberg, came to hear of it, he resolved to do something about it. Luther, like other theologians, had come to the conclusion that the way indulgences were being preached led people away from a true under-standing of the forgiveness of sins offered by Christ. But Luther went even further, for he began to doubt that the pope had the power of issuing indulgences at all. On October 31 -- the eve of the feast of All Saints -- in 1517, Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses (questions for debate) on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, announcing a public lecture and debate on indulgences and other matters.

Martin Luther was a persuasive preacher and popular university lecturer. He had entered the Augustinian order and become a priest against his father's wishes. To prove to his father and himself that he could be a priest, Luther tried to observe religious life perfectly. But though he took on severe penances and piled on many good works, he felt he could not earn God's favor. Even though his confessor spoke to him about God's mercy, offered through the crucified Christ, Luther still feared God terribly.

While still a young man, Luther had been appointed a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg. Studying St. Paul's epistles, Luther slowly came to the conclusion that God offered salvation to those who simply believed and trusted in his mercy. Luther came to think that salvation came by God's Grace through the gift of faith -- which the Catholic Churchtaught. Yet, Luther went on to deny that good works count for anything, even for those who have the Grace of God within them.

|

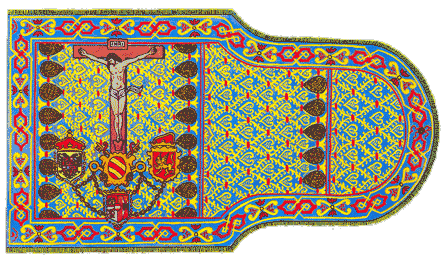

A detail from a pamphlet commemorating the Ninety-Five Theses. Luther holds a book that reads, Scrutamini Scripturas

("Search the Scriptures")

|

It was partly on account of this belief that Luther objected to indulgences -- for how, he said, can any good work we do remove any of the punishments for sin? In his Ninety-five Theses, Luther also complained that so much money, taken through the indulgence, was passing from Germany to Rome. Luther said that if the pope knew how poor the German people were, he would not take their hard-earned money even to build that new basilica over St. Peter's tomb.

The point about the money appealed to Germans, who for years had been taxed heavily by Rome. Luther did not stop with just posting his theses for debate; he had them translated into German from Latin and printed on that new invention, the printing press, and they were distributed throughout Germany. The theses quickly became very popular among Germans of all classes. It was not long before Luther's name became well known throughout Germany and even reached the pope in Rome. In 1518, the curia began the process that would end in the condemnation of Luther.

The foregoing is taken from our textbook, Light to the Nations I.

Additional Resources:

How the Reformation Happened by Hilaire Belloc

Roots of the Reformation by Karl Adam

The Catholic Reformation by Henri Daniel-Rops (out-of-print, check library)

History of the Reformation in Germany by Joseph Lortz (out-of-print, check library)

pe he will not leave us. Either Napoleon or I -- I or Napoleon; but we cannot rule together. I have already learned his character; he will deceive me no more."

pe he will not leave us. Either Napoleon or I -- I or Napoleon; but we cannot rule together. I have already learned his character; he will deceive me no more."