July 28, 1914:

The First World War Begins

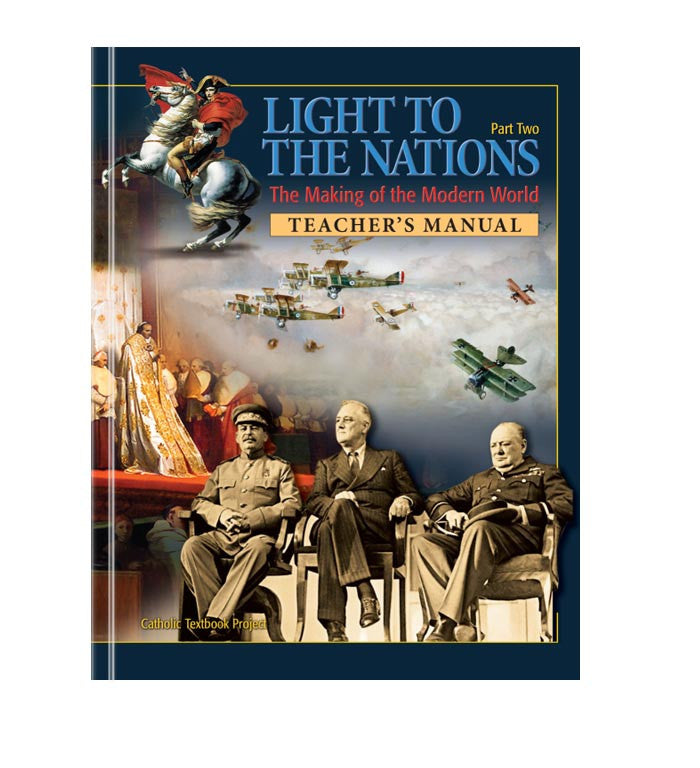

This week we commemorate the 100th anniversary of what proved to be the beginning of the "Great War," World War I -- Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia. The following comes from our book, Light to the Nations II: The Making of the Modern World. For ordering information on this text and our other books, please click here.

All of Europe protested the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie. Who could not sympathize with the aged Emperor Franz Josef, who had suffered so many tragedies in his life and now had to bear with the loss of his heir? Such an outrage demanded justice, and few European leaders would have blamed Austria-Hungary for seeking it.

|

| Emperor Franz Josef I |

But, besides the murderer himself and the Black Hand, who was responsible for the archduke's assassination? Though he had no direct evidence, Austria-Hungary's foreign minister, Count Leopold von Berchtold, was certain the Serbian government was ultimately responsible. Since 1913, Berchtold had been pushing for war against Serbia to end her attempts to draw the Slavs and Croats from the empire. The emperor had resisted these calls for war -- but would he continue to oppose war now that Serbia had sponsored such a foul murder? Berchtold was confident that he could now convince Franz Josef that war was necessary to stop Serbian violence against the empire.

The first step was to make sure that Germany would stand with Austria-Hungary. Though Kaiser Wilhelm II seems not to have wanted war at the time, he replied on July 6, 1914, that Germany would back Austria-Hungary in any action she chose to take against Serbia. Armed with this guarantee, Berchtold urged Franz Josef and Hungary's prime minister, István Tisza, to order a surprise attack on Serbia. The emperor, who still wanted peace, refused, as did Tisza. Knowing that both the emperor and Tisza feared that Russia would enter a war on the side of Serbia, Berchtold argued that Russia would not risk such a war. At last Berchtold suggested that an ultimatum should be sent to the Serbian government, making demands to which, Berchtold knew, Serbia would never agree. The old emperor, who loathed the thought of war, nevertheless agreed to the ultimatum.

|

| Count Berchtold |

The ultimatum sent to the Serbian government on July 23, 1914, accused Serbia of breaking her promise "to live on good neighborly terms" with Austria-Hungary. It then made a number of demands and said the Serbian government had to respond to the ultimatum in 48 hours. The response of the Serbian government was conciliatory; it agreed to all the demands made by Austria-Hungary, except for two that would undermine Serbia's sovereignty. In addition, Serbia suggested that the dispute be settled by The Hague court. But Serbia also ordered a partial mobilization of her army against Austria-Hungary the same day the reply was sent, which gave Berchtold a reason for saying the reply was insufficient. Austria-Hungary rejected Serbia's reply and ordered a partial mobilization of her own army, against Serbia.

Count Berchtold hoped that any war with Serbia would involve no other European power. Such a war, however, would put Russia in a difficult place. If Austria-Hungary were allowed to overrun Serbia, Russia would lose the confidence of the Slavic Balkan states. At the same time, war with Austria-Hungary would mean a war with Germany, which Russia did not want.

|

| European nations and their alliances in 1914 |

A war in the Balkans could create problems for France as well, for Russia would probably ask for French help if Germany entered the war on the side of Austria-Hungary. France did not want a war, but the French government feared that if it did not stand with Russia, France would lose a powerful ally. For this reason, French president Raymond Poincairé, visiting St. Petersburg on a state visit, assured Tsar Nikolai II that Russia could count on France's support in the event of a war with Austria-Hungary or, even, Germany.

|

| Tsar Nikolai II (left) and his cousin, King George V of Great Britain |

It was clear that the real threat to peace lay in a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia, which would almost necessarily include their allies, Germany and France. To prevent such a war, Great Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, on July 24, 1914, asked the great powers to convince Austria-Hungary and Russia to act reasonably. The French government rejected Grey's proposal. On July 26, Grey suggested a meeting between the ambassadors of France, Italy, Germany, and Great Britain in London; but this time Germany stood in the way, saying the dispute between Austria and Serbia concerned those two powers alone.

If, however, Germany refused to send delegates to London, she did put pressure on Austria-Hungary to open up talks with Russia. Count Berchtold, however, would hear nothing of talks, for he was intent on war. Berchtold's chief obstacle was the emperor. Franz Josef was opposed to war, even to "avenge" his nephew, the murdered Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Nothing his ministers said, it seemed, could change his mind.

Yet, in the end, the emperor did change his mind. Why, we do not know. He had received forged telegrams, falsely reporting that Serbian troops had invaded Austro-Hungarian lands. These reports may have convinced him that he could no longer avoid war. But whether it was the telegrams or some other cause, on July 28, 1914, the peace-minded Franz Josef agreed to a declaration of war against Serbia. The next day, the Austrian army began a bombardment of Serbia's unfortified capital, Belgrade.

Film Footage of the Emperor

This clip from a longer television documentary features film footage of Emperor Franz Josef I, as well as Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Archduke Karl von Habsburg, and Kaiser Wilhelm II. While the footage is indeed interesting, we do not vouch for the commentary.